According to Dawson (2017) rubrics come in various forms and are underpinned by a range of understandings. He has identified fourteen rubric design elements (or points of difference between them). The points of difference indicate the complexity in developing and understanding rubrics. This good practice guide (GPG) will provide insight into what a rubric is, common elements to include, the purpose for developing rubrics and different approaches to developing them.

What is a rubric?

A rubric is a tool which provides information about specific expectations related to an assessment task. It outlines the assessment’s individual aspects, providing “a detailed description of what constitutes acceptable or unacceptable levels of performance” against each aspect (Stevens, 2013, p. 21). Ideally, rubrics help students to identify links between their learning and what they are being assessed on. Rubrics should therefore be linked to learning outcomes.

There are some common elements included in most types of rubrics. These are:

- a short paragraph explaining the assessment to which the rubric refers

- the learning outcome being assessed

- standards/ levels (3 – 5, as discussed below these may include a score or grade)

- criteria or dimension (as discussed below these may include a percentage)

- agreed descriptions of the standard of performance against the criteria (Muhammad, Lebar & Mokshein, 2018)

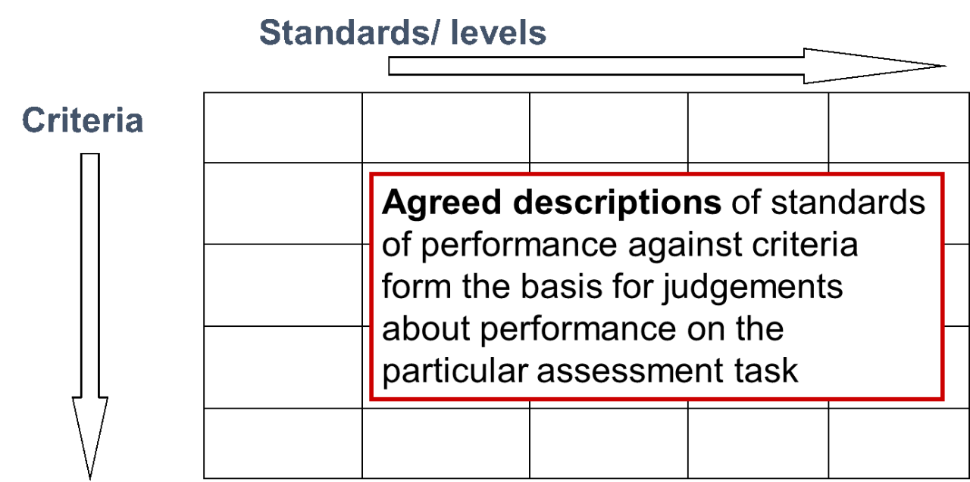

As shown in Figure 1: Rubrics ‘matrix’, rubrics are usually presented in a matrix or grid format with the horizontal axis providing a scale depicting progression against specific criteria (indicated in the vertical axis). The centre ‘squares’ include descriptions of how judgements about performance will be reached.

Figure 1: Rubrics 'matrix'

Purposes of rubrics

As discussed earlier, there are many types of rubrics and many purposes a rubric may serve (Muhammad, Lebar & Mokshein, 2018). Rather than trying to provide insight to all the kinds of rubrics and all their purposes, this guide focusses on understanding the value of rubrics and how they may be used to:

- help students determine how to achieve a desired grade

- support staff when marking students

- help students understand how they acquired the grade they received.

Although the development of rubrics can be time-consuming, a well-designed rubric that is discussed with students alongside the assessment instructions can minimise student frustration and time to understand what is required. Rubrics also save academics time in marking, providing feedback, and responding to questions about the assessment and how it was graded.

Help students determine how to achieve a desired grade

For students to achieve a desired grade, they need to know the criteria and judgements which will be used to determine their levels of achievement (or grades). A carefully crafted rubric will provide a rich source of information to the student, indicating how failing and exemplary grades compare, as well as the gradations between these extremes. Rubrics can therefore provide useful information to students about what they need to include as they develop their responses to an assessment. A rubric should always be provided to students before they begin work on an assessment. The example rubric provided below demonstrate how students might see various grades differentiated and determine what they need to include.

Support staff when marking students

Just as rubrics make transparent the criteria and judgements which will be used to determine different levels of achievement and how to attain them, the same information is also made clear to those marking assessments. Rubrics therefore provide a way to support the marking process and allow less variation across grades (especially where different markers are assessing different student submissions). Reducing marker variation leads to less student confusion and increases assessment validity.

Help students understand how they acquired the grade they received

Providing both students and marking staff with transparent grading criteria and standardised, consistent feedback should ensure there is less confusion about how a grade is determined. Standardised feedback helps students understand academic expectations (across different areas of study) and allows them to see how they acquired a grade; this supports the development of assessment and feedback literacy in students.

According to Orrell (2020, p.3) “higher education courses are responsible for developing student thinking and reasoning so that they leave higher education functioning at a higher level of thinking than at that which they entered.” Therefore, it is useful to provide students with a guide (rubric) that allows them to assess how well they have met specific criteria linked to learning outcomes. Rubrics can support learning by providing students with information about both what they have learned and how well they have learned it. Once they become more astute at using rubrics, students will be able to judge their own work and identify their own gaps in learning.

Different approaches to developing rubrics

There are many approaches to the development of rubrics. The approaches include:

- providing a potential mark or grade value against the standards/ levels (or not)

- indicating percentages against the criteria (or not)

- providing both a mark or grade value and percentage

- indicating different levels of detail in relation to standards or levels (Muhammad, Lebar & Mokshein, 2018)

- direction taken by standards/ levels (left to right or right to left) may differ

- developing a holistic or analytical rubric

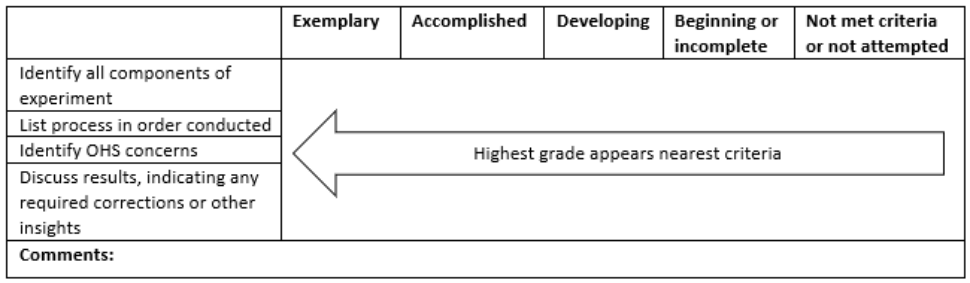

There are different views regarding the direction the standards/ levels take. Many argue that starting with the lowest grade on the left and increasing to the highest grade on the right is a more logical presentation (as indicated in both Figure 1 and Table 1). However, as indicated in Figure 2, others suggest that placing the highest possible grade on the left next to criteria allows students to immediately see how to achieve the highest grade.

Figure 2: Highest grade appers nearest criteria

Different types of rubrics

The University of Edinburgh (Scotland) and the University of Waterloo (Canada) discuss holistic rubrics (where the actions required to achieve a performance level are provided beneath it) and analytic rubrics (where specific detail on performance is provided in relation to each assessment criteria). Both sites provide various examples.

Table 1 below shows an example assessment rubric (analytical rubric) which has been designed for an assessment that many may use with first-year, first-semester students. It is not perfect (none are), its purpose is to demonstrate how to include many of the essential elements when developing a rubric: a potential grade value; percentage assigned to different criteria and to the assessment; different levels of detail regarding standards; learning outcomes and an opportunity for the assessor to make further comments. The name of the assessment (brief description) is also provided as is the suggestion that students also access detailed instructions on how to complete the assessment. Designing an assessment rubric provides further discussion on using generic rubrics and includes an example of one.

In general, each assessment task will need its own rubric, designed or adapted for the specific assessment context. When developing a rubric, it may be useful to work from a checklist to ensure that key considerations have been contemplated, including:

- ensure your assessment task, and thus, the rubric, addresses the topic learning outcomes and makes use of an appropriate taxonomy (e.g. Bloom’s or SOLO)

- decide on the rubric type - do you want a holistic rubric (where the actions required to achieve a performance level are provided beneath it) or an analytic rubric (where specific detail on performance is provided in relation to each assessment criterion)?

- outline rubric components – the assessment task, criteria to be used, the scale and the scale descriptors.

- prior to use, ask for feedback from peers to ensure the descriptors are clear, unambiguous and link to the learning outcomes for the assessment task and the topic.

- consider the format through which the rubric will be delivered – will you use an online rubric via Speedgrader in FLO, or one that will need to be uploaded to FLO? Depending on your format preferences, you may be presented with varying construction options.

Caveats

Menéndez-Varela and Gregori-Giralt (2018) note that rubrics “do not include the implicit processes of judgement that are also included in assessment” (p. 71), and because students and staff may interpret the rubric criteria in different ways, rubrics may cause confusion regardless of their intended clarity and transparency.

To avoid errors in judgement and misunderstandings it is best to have the rubric moderated then discussed with markers and students before work on or marking of the assessment begins. Discussing the rubric, assessment instructions and your expectations with students (and markers) before they begin attempting the work is also a helpful way to guide learning. Once the assessment is submitted and marked, returning it with the annotated rubric alongside other forms of feedback will guide students’ learning.

Rubrics in FLO

When using rubrics in FLO there may be some differences in the way you set them up. These can be discussed with your local learning designer or you can refer to the Canvas Staff FLO Support guides, Canvas Instructor Guides, and the guide on setting up an online rubric on FLO.

In summary

This good practice guide has discussed what rubrics are, their common elements and purposes as well as different approaches to their development. It has outlined the different types of rubrics and various approaches to developing them. The main message of the guide is that while no rubric is perfect, a well-designed one can support learning, help students understand the grades they have achieved, and guide marking for academic staff. When used appropriately they can save time and reduce student complaints. They are usually presented in a grid or matrix format and include a scale depicting progression against specific criteria with standards of performance indicated within the grid. Rubrics ideally indicate the learning outcomes being assessed and are discussed with students and markers alongside assessment instructions before the assessment is attempted.

Your academic developer can provide further support and advice on developing a rubric while your learning designer can help you use rubrics within FLO.

Using Library databases to search for journal articles and develop a reference list

(Assessment 1) Grade: (30%)

Please also refer to the detailed instructions provided separately for further explanation of what to do.

Meets learning outcomes: LO2 Evaluate resources using critical thinking skills and LO3 Assess the value of literature to support an argument/discussion.

|

Not met criteria or not attempted (F) |

Beginning or incomplete (P) |

Developing (C) |

Accomplished (D) |

Exemplary (HD) |

List keywords and synonyms related to question chosen for database search (15% of total grade for this assignment) |

No keywords presented |

Words used in the search were included but these were not key to identifying resources to answer the chosen question |

The listed words comprise a mix of keywords and words which may not support identifying resources to answer the chosen question |

The listed keywords are clearly related to the chosen question although there are no synonyms included |

The listed keywords are clearly related to the chosen question and synonyms are included |

Briefly describe process undertaken for database searches (15%) |

No processes described and/or no searches presented |

Either the search or the description of the process undertaken to complete the search is missing |

Searches and a description are present, but it does not provide insight into how the database search was conducted |

The searches and description indicate an accurate understanding of how to conduct database searches |

The searches and description indicate an accurate and complex understanding of how to conduct database searches |

Display references chosen for assignment using APA (30%) |

No references presented |

References present but were not cited using the required referencing style, and/or information was missing |

References present and displayed using the required referencing style, but information was missing |

References present and displayed using the required referencing style, although some inaccuracies or inconsistencies are present |

References displayed using the required referencing style, with all information accurately presented |

Write a succinct paragraph reflecting experience, including content and focus of chosen database and provide helpful tips on using the chosen database(s) (40%) |

No paragraph reflecting experience included |

The paragraph did not reflect experience of searching and the task was incomplete |

The paragraph did not reflect experience of searching OR content and focus of database(s) was not included OR the tips were not described in enough detail to be helpful |

The paragraph included all elements. It would be improved through further discussion on the content and focus of database(s) or by describing the tips in more detail |

The paragraph succinctly discussed: content and focus of database(s) as well as helpful tips on using them. The task was completed beyond basic expectations by including a discussion about what was important and why |

Further comments

|

|||||

Dawson, P. (2017). Assessment rubrics: towards clearer and more replicable design, research and practice. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(3), 347-360. doi:10.1080/02602938.2015.1111294

Menéndez-Varela, J.-L., & Gregori-Giralt, E. (2018). Rubrics for developing students’ professional judgement: A study of sustainable assessment in arts education. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 58, 70-79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2018.06.001

Muhammad, A., Lebar, O., & Mokshein, S. E. (2018). Rubrics as Assessment, Evaluation and Scoring Tools. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8, 1417–1431.

Orrell, J. (2020). Designing an assessment rubric. Online learning good practice series. Available: https://www.teqsa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-10/designing-assessment-rubric.pdf

Stevens, D. D. (2013). Introduction to rubrics: an assessment tool to save grading time, convey effective feedback, and promote student learning. In A. Levi (Ed.), (2nd ed. ed., pp. 21-30). Sterling, Va.: Stylus Publishing. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/flinders/detail.action?docID=1108395.